About Zdzisław Beksiński - biography, techniques, facts, quotes, photography and more

"I wish to paint in such a manner as if I were photographing dreams."

- Zdzisław Beksiński

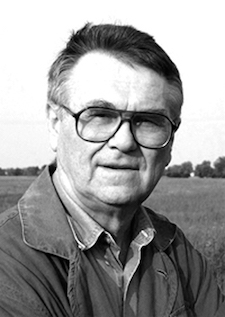

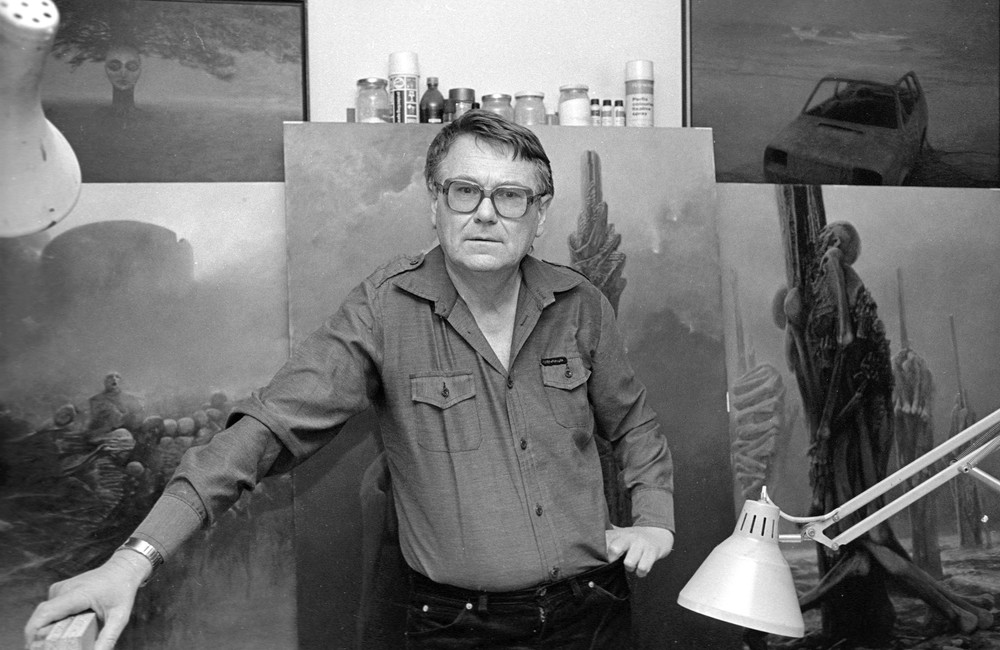

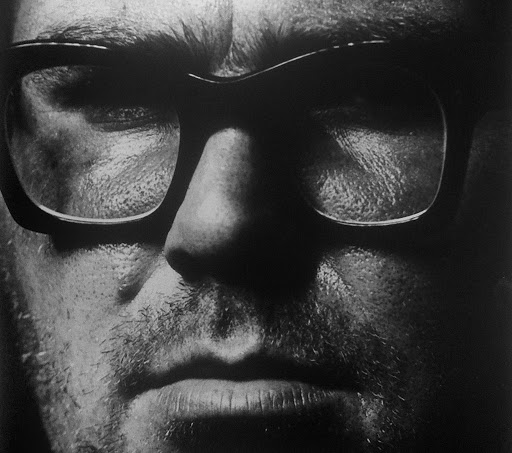

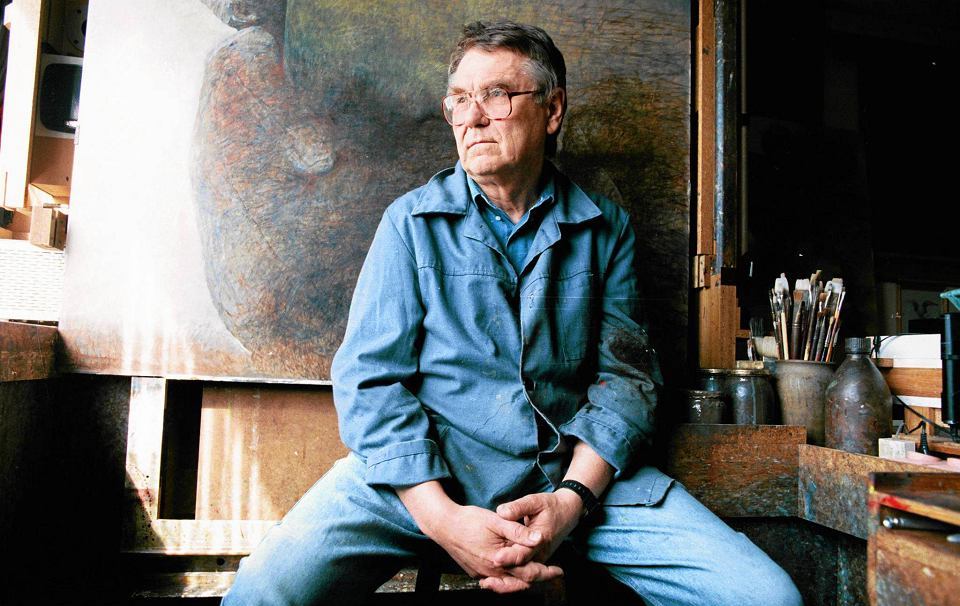

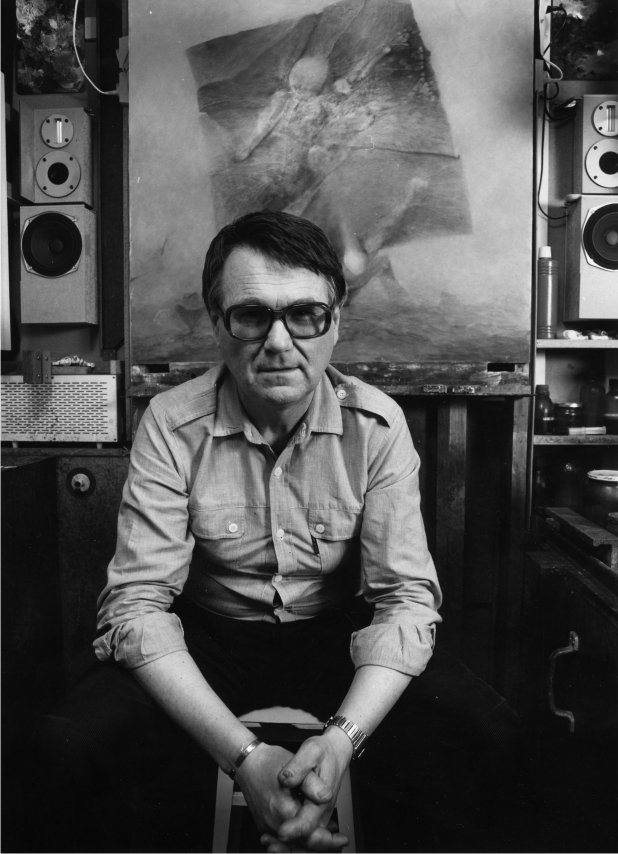

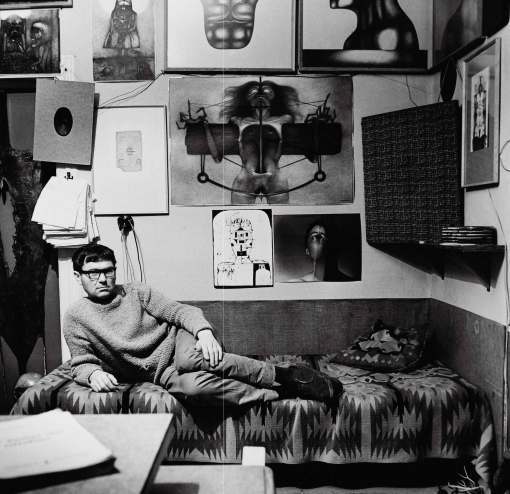

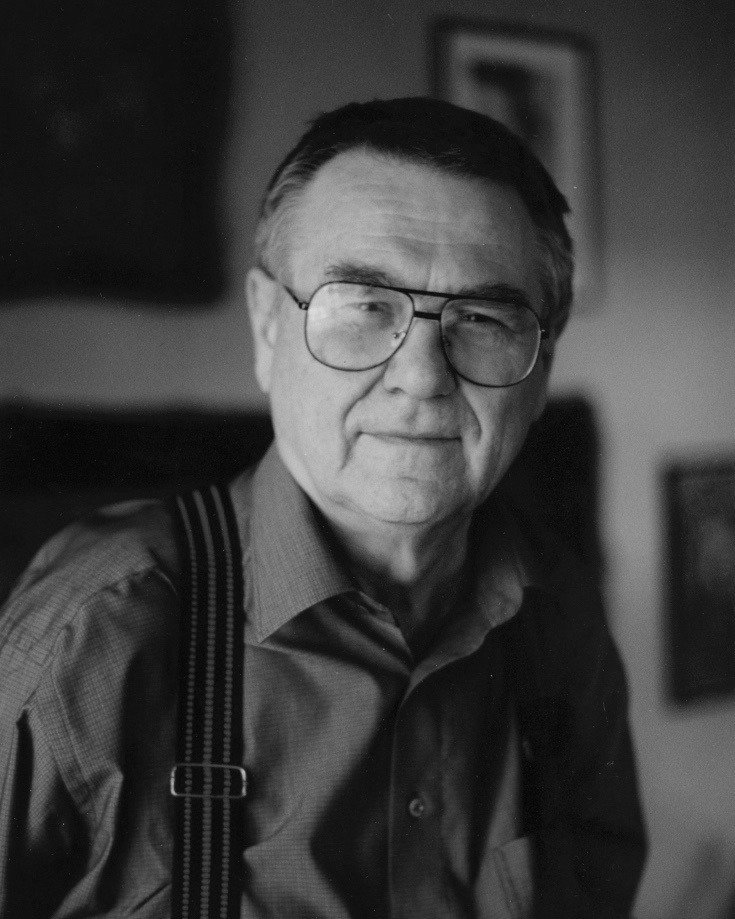

Zdzisław Beksiński (24 February 1929 – 21 February 2005) was a Polish painter, photographer and sculptor, specializing in the field of dystopian surrealism. Beksiński made his paintings and drawings in what he called either a 'Baroque' or a 'Gothic' manner.

Life and early work

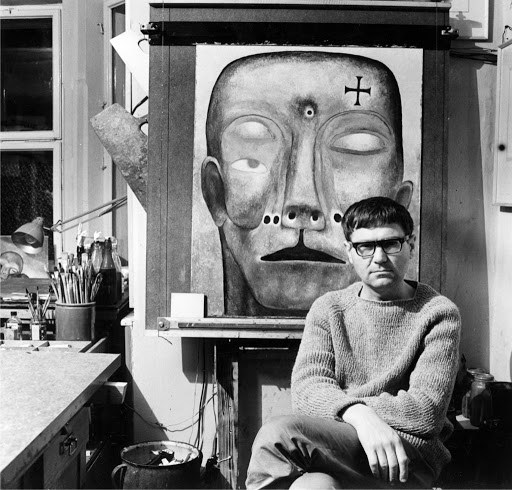

Zdzisław Beksiński was born in Sanok, southern Poland. He studied architecture in Kraków. In 1955, he completed his studies and returned to Sanok, working as a construction site supervisor, but found out he did not enjoy it. During this period, he had an interest in montage photography, sculpting and painting. When he first started his sculpting, he would often use his construction site materials for his medium. His early photography would be a precursor to his later paintings often depicting peculiar wrinkles, desolate landscapes and still-life faces on rough surfaces. His paintings often depict anxiety, such as torn doll faces, faces erased or obscured by bandages wrapped around the portrait. His main focus was on abstract painting, although it seems his works in the 1960s were inspired by Surrealism.

Beksiński had no formal training as an artist. He was a graduate of the Faculty of Architecture at the Kraków Polytechnic with MSc received in 1952. His paintings were mainly created using oil paint on hardboard panels which he personally prepared, although he also experimented with acrylic paints.

Career

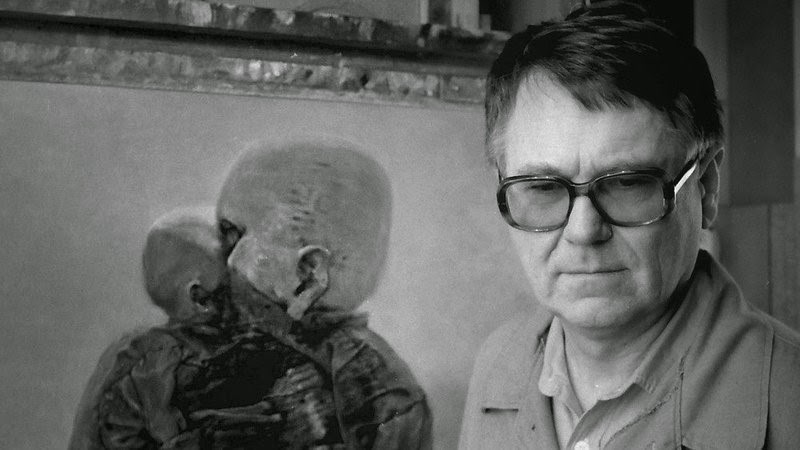

His creations were made mainly in two periods. The first period of work is generally considered to contain expressionistic color, with a strong style of "utopian realism" and surreal architecture, like a doomsday scenario. The second period contained more abstract style, with the main features of formalism.

[Untitled (commonly known as "The Flutist", "The Flute" or "The Horn"), Zdzisław Beksiński, 1983]

An exhibition in Warsaw in 1964 was his first major success, as all his paintings were sold.

Beksiński undertook painting with a passion, working intensely and whilst listening to classical music. He soon became the leading figure in contemporary Polish art. In the late 1960s, Beksiński entered what he himself called his "fantastic period", which lasted up to the mid-1980s. This is his best-known period, during which he created very disturbing images, showing a gloomy, surrealistic environment with very detailed scenes of death, decay, landscapes filled with skeletons, deformed figures and deserts. These paintings were quite detailed, painted with his trademark precision. At the time, Beksiński claimed, "I wish to paint in such a manner as if I were photographing dreams".

Despite the grim overtones, Beksiński claimed some of his works were misunderstood; in his opinion, they were rather optimistic or even humorous. For the most part Beksiński was adamant that even he did not know the meaning of his artworks and was uninterested in possible interpretations; in keeping with this, he refused to provide titles for any of his drawings or paintings. Before moving to Warsaw in 1977, he burned a selection of his works in his own backyard, without leaving any documentation on them. He later claimed that some of those works were "too personal", while others were unsatisfactory, and he didn't want people to see them.

[Untitled, Zdzisław Beksiński, 1978]

What I'm after is for it to be obvious at first sight that this is a painting I made.

The 1980s marked a transitory period for Beksiński. During this time, his works became more popular in France due to the endeavors of Piotr Dmochowski, and he achieved significant popularity in Western Europe, the United States and Japan. His art in the late 1980s and early 1990s focused on monumental or sculpture-like images rendered in a restricted and often subdued colour palette, including a series of crosses. Paintings in this style, which often appear to have been sketched densely in coloured lines, were much less lavish than those known from his "fantastic period", but just as powerful. In 1994, Beksiński explained "I'm going in the direction of a greater simplification of the background, and at the same time a considerable degree of deformation in the figures, which are being painted without what's known as naturalistic light and shadow. What I'm after is for it to be obvious at first sight that this is a painting I made".

In the later part of the 1990s, he discovered computers, the Internet, digital photography and photo manipulation, a medium that he focused on until his death.

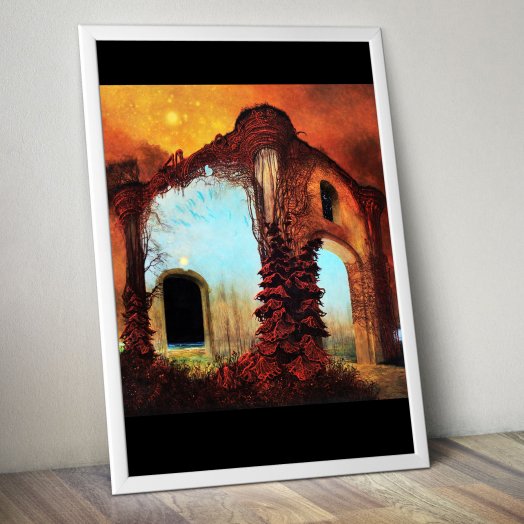

[Untitled (commonly known as "Cathedral"), Zdzisław Beksiński, 1983]

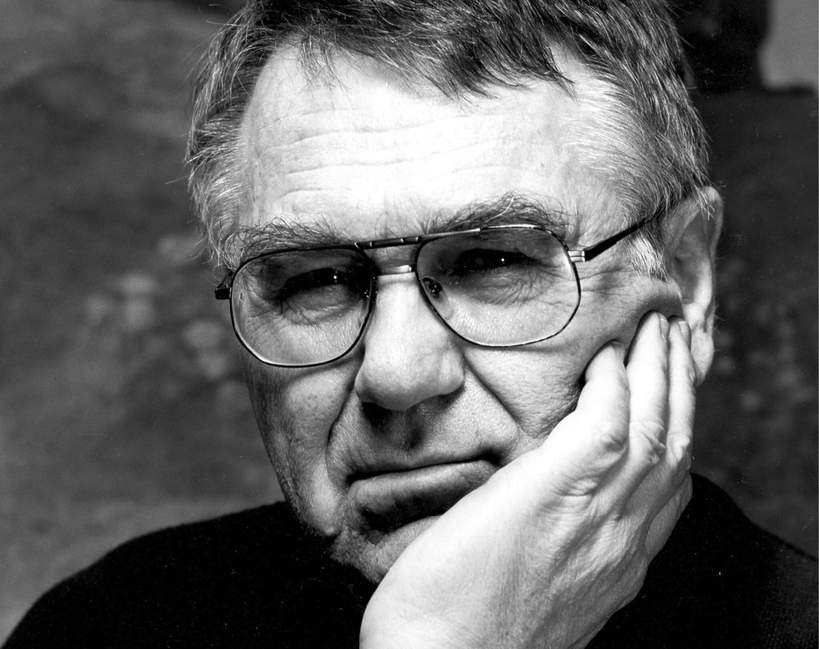

Personality

Although Beksiński's art was often grim, he himself was known to be a pleasant person who took enjoyment from conversation and had a keen sense of humor. He was modest and somewhat shy, avoiding public events such as the openings of his own exhibitions. He credited music as his main source of inspiration. He claimed not to be much influenced by literature, cinema or the work of other artists, and almost never visited museums or exhibitions. Beksiński avoided concrete analysis of the content of his work, saying "I cannot conceive of a sensible statement on painting". He was especially dismissive of those who sought or offered simple answers to what his work 'meant'.

[Untitled (commonly known as "Soldier"), Zdzisław Beksiński, 1985]

Later life and death

Beksiński's wife, Zofia, died in 1998; a year later, on Christmas Eve 1999, his son Tomasz (a popular radio presenter, music journalist and movie translator) committed suicide. Beksiński discovered his son's body. Unable to come to terms with his son's death, he kept an envelope "For Tomek in case I kick the bucket" pinned to his wall.

On 21 February 2005, Beksiński was found dead in his flat in Warsaw with 17 stab wounds on his body; two of the wounds were determined to have been fatal. Robert Kupiec, the teenage son of his longtime caretaker, and a friend was arrested shortly after the crime. On 9 November 2006 Robert Kupiec was sentenced to 25 years in prison, and his accomplice, Łukasz Kupiec, to 5 years by the court of Warsaw. Before his death, Beksiński had refused to loan Robert Kupiec a few hundred złoty (approximately US$100).

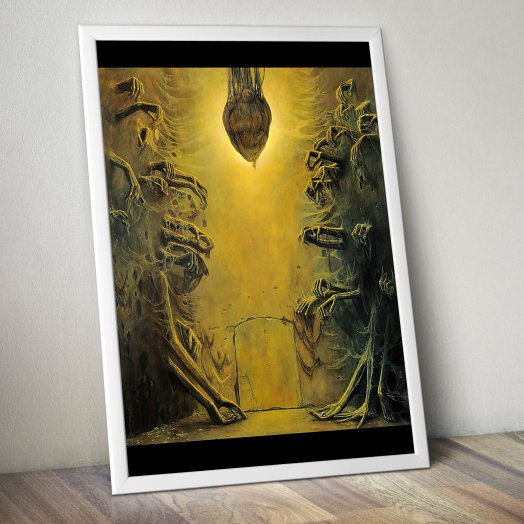

[Untitled (commonly known as "Heart"), Zdzisław Beksiński, 1976]

Curious facts about Beksiński

Beksiński graduated from architecture at the AGH University of Science and Technology in Cracow

After high school graduation, he applied for both architecture and fine arts. However, he chose the architect’s career path and after many years he said: “That’s why I hated architecture so much that architecture is a plan, a project and a boring as a mechanical saw execution”.

During 1959-1970 he worked at “Autosan” (Polish bus and coach manufacturer) as a so-called visual artist, a person responsible for bus design

Most of his projects, after creating prototypes, did not enter into production. He worked part-time for six hours a day and he had free Saturdays. He devoted the remaining time to his artistic activity.

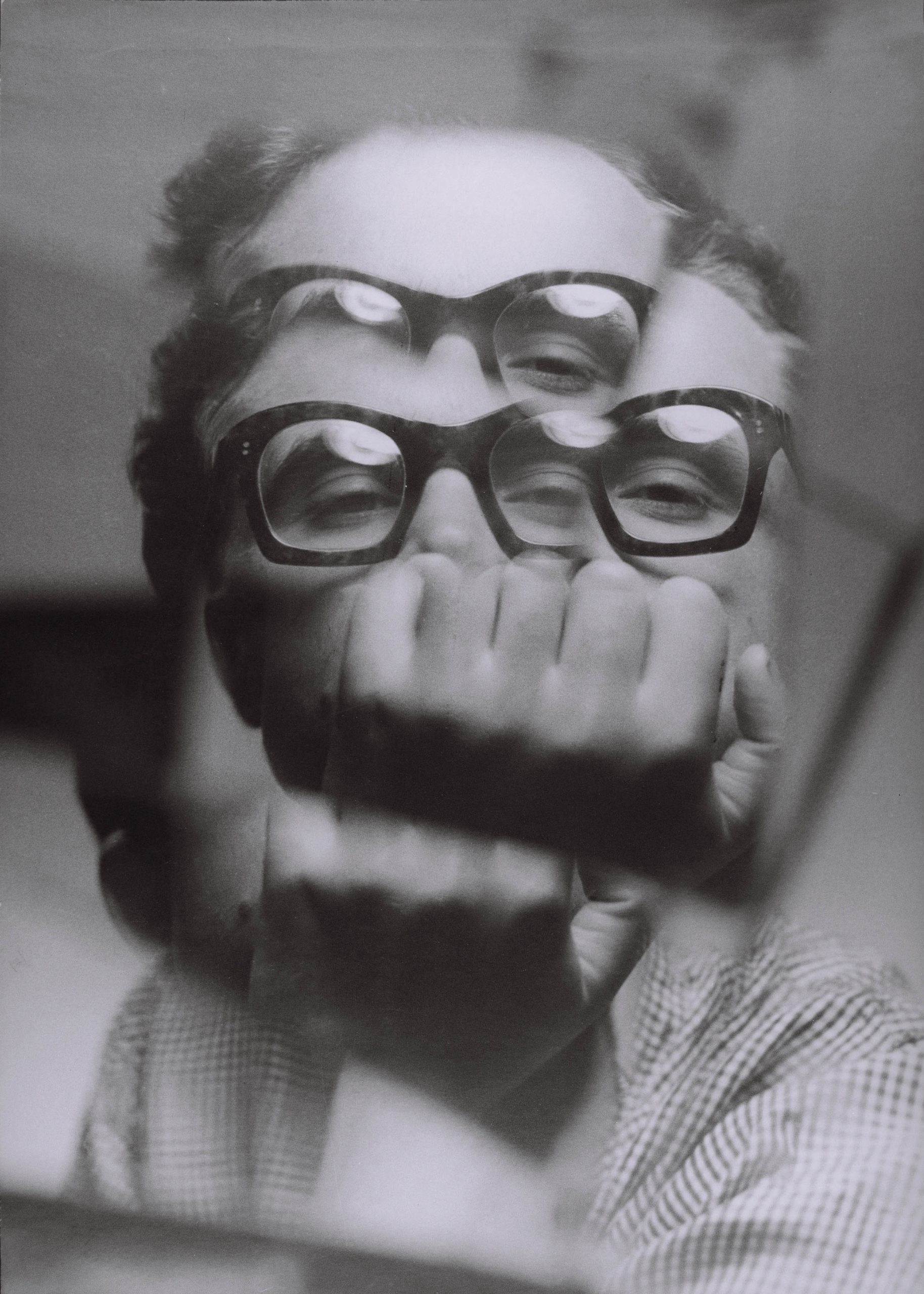

Photography

Despite the fact that currently Zdzisław Beksiński is known mainly as a painter, his career began with photography. Formally he even belonged to the Polish Photographic Society in Sanok since 1955, and three years later he also joined the Union of Polish Art Photographers (ID number – 237).

He refused to accept a six-month scholarship of the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1961

In 1960, the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) took place in Poland. As part of it, invited critics from around the world also visited Cracow and the biennial dedicated to graphics, the exhibition of folk art and painting which were prepared for this occasion. One of the exhibitions was prepared by the Polish member of AICA Janusz Bogucki and Zdzisław Beksiński took part in it. The exhibition was visited by the president of AICA and the director of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, James Johnson Sweeney, and probably he offered Beksiński a scholarship. However, the artist refused to leave Poland.

After a few years, he said: “I refuse to travel, which (Bogucki) does not understand, because like every Pole, he wants to travel and to have a car and thinks that everyone must have the same. (…) And I just want to tinker, and I have a eudaimonistic point of view and I used to do what I like and not what I need.”

He suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder since his youth

Neuroses have changed over the years, but one remained constant: “my life is dominated by a neurotic diarrhea, and that’s it. Hence my reluctance to travel and it remains indifferent whether the journey concerns deportation to Siberia or yacht trips around the world. (…) EVERYTHING that separates me from the BASE (which is a house or an apartment that I own) exposes me to a specific conditioned nervous tension“. For this reason, he tried to avoid any changes, travels, unannounced visits or unexpected events as often as possible.

He was passionate about computers

His interest began in 1986 with Casio minicomputers, and since then he was buying every new product entering the IT market, and he distributed older items to his family and friends. In Poland of that time, he had the most modern equipment, and his knowledge was comparable to the expertise of qualified IT specialists.

He was experimenting and creating art using new technologies. He started with a photocopying technique

As he described it himself: “I photocopied some drawn things, then I covered some fragments with white or black paint and I photocopied them again, etc. With time, thirty prints led to the thirty first one, which was the final print. This allowed you to make some variants. For example, there were characters that had some common elements, but the rest were different. A whole cycle of figures sitting and talking was created.”

‘Domestic animals’

Zdzisław Beksiński was a very prolific artist, usually creating several dozens of works a year. Most of them he sold or tried to sell or give away to family and friends. However, he left some of them for himself hanging them on the walls of his flat or of apartment of his son Tomasz. He called this private collection “domestic animals”.

Beksiński did not participate in his vernissages.

“Hundreds, if not thousands of times, I have emphasized that I do not go to the openings of my own and not my own exhibitions, because it is a terrible stress for me! I cannot stand such situations.” However, he did not have a bigger problem with interviews: he was interviewed at least once each year.

Music

The artist’s studio was always equipped with a music-sound system, which Beksiński liked to listen to loudly and even very loudly. In the mid-1970s, he built his own recording studio in his home in Sanok. He almost always created with music, and a few years later he started wearing a hearing aid.

“When I paint while listening to pop music, I make movements with my torso, which hinders my work, seemingly senseless; nevertheless, turning off the sound system creates a feeling of lack of something, without which you cannot work. And that is why it does not matter what I paint – what is important is what I cannot express in words, but I hope I can express it in some of the best paintings. Some kind of indeterminate, but (…) existing exultation, which is most strongly present in post-Wagner’s music.”

How to paint like Beksiński

Beksiński wrote at length about his workflow and technique:

I paint with Rowney's paints "ARTIST OIL COLOURS" and Talens' "REMBRANDT ARTIST OIL COLOURS", as well as Rowney's "CRYLA - ACRYLIC" and Talens' "REMBRANDT-ACRYLIC".

For each painting I use a certain amount of colors, do not go beyond that.

As for the brushes I use only those that I have and which I could afford. There are better but I failed to buy.

Brushes I use are almost entirely flat and hard, that is, either from pig bristles or nylon. Of course with several gradations of hardness and with various hair length. Minor trims, finishings and small brightenings paint with small number, round sable brushes. But that's just when finishing off the image in just a few places.

Paints are not divided into red or blue, but into expensive and cheap. Some red are cheap, some blue as well and the opposite too. The same applies to other colors. Next, there are whole "series" expensive or cheaper.

The most expensive paints are "artistic", the cheaper are "for artists", more cheaper are "budget", even cheaper "to study", the cheapest "for schools".

I paint with paints absolutely most expensive (as the series), but when it comes to the colors, I do not go by the price! In Polish conditions, buy them in large amounts, paints in Poland are hard to get, I get them thanks to people. [note: Beksiński wrote this during communist era in Poland.]

I am not guided in choosing colors with nothing but imagination and the persistence of what I do to light. Resign of certain color because it's unstable or can not be mixed with all others or threatens that will respond to hydrogen sulfide from the atmosphere or free fatty acids in linoxide.

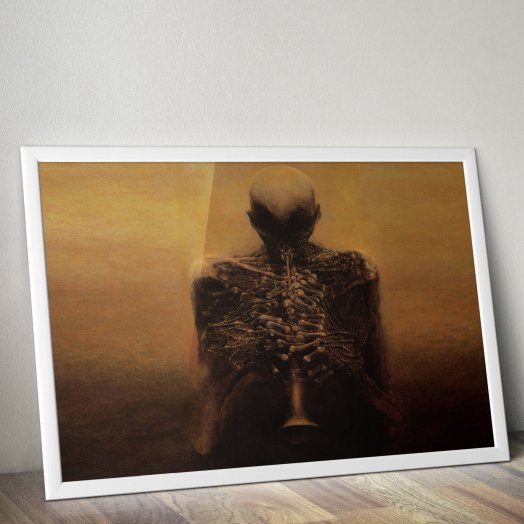

[Untitled, Zdzisław Beksiński, 1978]

Modern chemistry has given us better paints than old masters had. Only the painters are worse.

The paints produced by good companies are divided into: "absolutely stable", "stable", "stable with limitations" and "unstable". I do not purchase at all paints that are "unstable" even though they are the prettiest. They are produced due to tradition of using certain pigments, but they slowly becoming obsolete.

I have paints "stable with limitations" but never used them (eg: white leaded, Prussian blue etc.) because they hinder the work. Can not be mixed with any other paint but only selected ones, for example they are sensitive to hydroxides etc.. I use "absolutely stable" and "stable" paints only. They are all chemically neutral and can be mixed together in any proportion. Between them both there is this difference that paints "absolutely stable" does not change under any influence over the millennia (ochers, cobalts, iron reds, etc.). However "stable" may slightly fade if they were exposed to the direct sunlight for hundreds of years, or worse, further brightened with white and then fried in the sun.

But what we now call "stable" paints had neither Leonardo nor Ucello and they're so damn resistant to light.

I checked myself red and violet cadmiums (painted in a thin layer) exposing them through a thin window for over two years in direct sunlight and nothing happened - any perceptible change.

Modern chemistry has given us better paints than old masters had. Only the painters are worse.

More damage to painted images causes darkness, especially works with the bright colors and painted with bluish and white.

Dried linseed oil - linoxide [note: linoxid? - the product of oil oxidation] darkens due to the lack of light (as seen for example on the doors painted in white, if it has a calendar hanging on it). There is a conservation technique of lightening old, yellowed images due to holding them in the basement, using the quartz lamp exposure, because darkened linoxide can get slightly lighter this way (and then darkens again, if there is no light). Because this darkening has a character of yellowing and browning after years, the paintings with brown, yellow and red colors are less exposed to visible changes, than blue, white and steel. And in any case the latter must always be kept in the light - then the changes are less visible.

All this does not apply to acrylics. Pigments are the same, but there is no yellowing. However, not everything can be paint with acrylics and it is mechanically easier to dirt and more difficult to clean. It is simply because acrylic painting is porous and dirt gets in these microscopic pores and can not be removed.

How to varnish a painting like Beksiński

Beksiński about his varnishing process:

I did not use acrylic varnish

After about three months after completing the picture I cover it with alkyd resin in polymerized oil, ie. LIQUIN (produced by Winsor and Newton). I wait as long as I can with this procedure, because Liquin must be rubbed very strongly with sharp nylon brush, and if the picture is fresh there is a risk of smudging some colors. Besides, the later you put it on the painting the slower it tarnishes and penetrates into the picture. Then it is allowed to photograph the painting, because then it has its surface compensated in terms of glossing. After a year or better after two years, the painting can be varnished.

I did not use acrylic varnish, and besides, it is not suitable for oil paints (it's such a milk - an aqueous dispersion of acrylic resin). Varnishing the oil painting requires skills of course, and glossy varnish in principle (if not used prematurely) do not tarnish (become mat) over time. This does not require preparing any special potions, and I would hesitate even to use them, as the varnishes produced today are at a very good level. The principle of good damar varnish is its no yellowing and no cracking over time and dissolving in solvents easy, so that any removing of it after years would not damage the painting itself.

Beksiński speaks about varnishing on another occasion:

(At the beginning of the 80s) I was experimenting with acrylic painting and carried out some tests. Acrylic painting generally is not suitable for varnishing. Pure acrylic painting is easy to distinguish by the fact that it is mat (unpolished). Although it can be seen some disruption of the opacity in terms of brush strokes, but all of these strokes are mat.

Generally problem of varnishing lies in the fact that the picture painted matt has some color proportions and qualities that would go to hell when it'll gain gloss.

Colors would become more vivid but uglier. This applies to all matte acrylics.

Varnish will not damage them materially, but will change them and could not be removed. So returning to its original state (before varnishing) won't be possible.

The so-called matt varnishes are generally crap, so I do not recommend them.

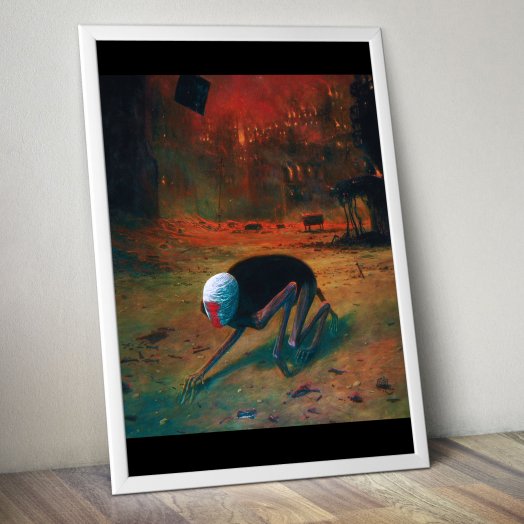

[Untitled (commonly known as "Night Creeper"), Zdzisław Beksiński, 1975]

Zdzisław Beksiński Q&A

Q: You have graduated as architect, so how has it come that you are a painter?

Zdzisław Beksiński: Generally speaking, the answer is quite simple. I am incapable of working in a team. Architecture implies collective work. If I could build quite on my own and for myself, I would be an architect in the same way as I am a painter. I enjoy only individual action. I do not care on what scale. Perhaps I would be happier producing large wall paintings, but only if I owned the paint and the wall and if the deadline, the manner of execution and everything else depended entirely on myself. The case being different. I prefer small pictures that fit a room and that are painted in a crammed studio. If I accepted a commission, I would be anxious to satisfy my employer. So why take on such obligations?

In my case, painting is like running a factory

Q: In the late 1950s you were an innovative photographer and produced metal reliefs, consistent with the spirit of contemporary avant-garde. So why did you give up that line a few years later and dedicated all your time to drawing and later to painting of a irrational character?

Z.B.: Questions beginning with "How did it happen..." are always the most difficult to answer. In retrospect, we tend to forget motives which prompted our decisions. For instance, I have not done a single drawing for five years, but always wanted to return to it as soon as I had finished the next two paintings which I had the fancy to finish, and then the next two. Then, for a change, I would no longer feel inclined to draw, then a year passed, and then another year and it is quite probable that I shall not draw in the coming ten years. Then, in another interview, I shall have to explain why I have given up drawing. Something similar has happened with photography. I still have all the equipment and even from time to time buy something new. Occasionally, it occurs to me that a good many things could be done mainly by means of photography, but in fact I feel more and more detached from it. There is no reason to deceive myself: I am almost sure that I shall not return to photography. It is a long time since I last did it, different stereotypes have meanwhile made their impact; finally, technological inertia acts as a drawback. In my case, painting is like running a factory: I have to provide myself with material, I have to equip my studio, etc., etc. The evolution of my vision and imagery is yet another matter. It is a very slow and fluid process, too. I would say the moment when I worked in accordance with contemporary avant-garde was the second stage in my career. I started as an expressionist, just as did many young Polish painters at that time. I did not know any of them. Nevertheless, what I did at then and what seemed to flow right from my "soul" was almost identical with what they did: silhouettes crying in the wilderness, people with heads of stone, women in labour, people caught in the acts of copulation, defecation, death, in front of a firing squad or on the gallows, in prison, towns without windows, and so on, and so forth. Stylistically, there was something of the spirit of Cwenarski and Wroblewski in it; I was even able to produce as many as five large-size paintings a day, I was absolutely uncritical, I got bored easily and saw no point in putting finishing touches to what had been very quickly daubed in distemper or charcoal on a large cardboard sheet. And yet, I think that it was only then that I have been really sincere. Or perhaps merely naive? Because later came a period of reflection and I saw that I had not the first to discover expressionism, nor the first to think that life was senseless. I even began to be a little ashamed of myself and wanted to be even more detached that I had been unrestrained in my outcry. I believe that my joining the avant-garde was, in fact, the first mask I have put on. It does not mean that I had changed my views but, ashamed that I had been a fool, I adopted a style as a mask. And I adopted a style that was in the lead. But I do not think that I owed really much to what I saw in other people's work. In fact, I have never been very interested in what others do. There must be some incidental factors which affect everyone alike and cause all the works of art created in a given period to appear fairly similar. Today, I am not surprised, that I was blamed for imitating people of whose existence I had never heard because my paintings, or rather reliefs of that period, were not much different from the average national production. Then came the third change leading towards my present work. I think that I felt rather uncomfortable in the mask I wore but, at the same time, my road towards naive sincerty was closed too, so I chose something which seemed to be another mask, though less uncomfortable. This is not the whole truth but one would need thousands of pages to explore and describe all the sources of this particular sequence of events. Even then it would not exhaust the subject.

[Untitled (commonly known as "Lovers"), Zdzisław Beksiński, 1984]

Q: While changing the direction of your research, did you not feel that, perhaps, there was not much hope for you in the field of avant-garde and you would not be able to establish your individuality by means you had used hitherto?

Z.B.: I think that one can fulfil oneself to the same degree in any style. When I welded my iron reliefs, I would often realize that I envied the painters of the past their neat studios which smelled of paint and I was overcome by the naive, simple need to paint at the easel. Of course, it turned out later to be as terribly hard work as the welding of iron sheets.

Q: What role of the Boguckis' Gallery play to stimulate your art? For many years the Boguckis were the sole organizers of your exhibitions.

Z.B.: With my total inability to organize career I do not think that I would have had a single exhibition had it not been for the Boguckis. I first met them in the 1950s, when I was a photographer who did a little bit of drawing and a little bit of painting. When they were mounting a photographic exhibition, a friend of mine literally dragged me to the Boguckis' flat in Cracow, together with a few other photographers. I must have had some photographs of my painter's beginnings on me - I do not remember details now. Then for a few years, I probably woried the life out of the Boguckis who were anxious to promote my work - a task as rewarding as rubbing a cat the wrong way. Like all maniacs of their own art, I was absolutely crazy about protecting my works from damage. I raised thousands of obstacles of which I am now quite ashamed, but at that time I was afraid they were irresponsible people, likely to waste all I had done, prompted by a passing fancy... I have not changed much: I still hate exhibitions.

Q: At the time of your avant-garde structural research, you made a superb relief with the motif of the cross, entitled "Malte" after Rilke. To what extent is literary inspiration responsible for the transformation in your art?

Z.B.: I cannot say much about that period in my career. If I remember rightly, the title could have easily been different and there would have been nothing wrong, at least from my point of view, if the painting had not been called "Malte". To my memory, the painting was not a fully successful materialization of visions which occurred to me during the reading of Rilke. I said "not fully successful" in the sense that I have never succeeded in painting or drawing exactly what I wanted. The result was and always is different from my intention, it always goes somewhat askew. Luckily those who see my work are not aware of it, but let me assure you that it is a terrible feeling not to have a single painting exactly as I wanted it to be. When I was ready with the relief, I named it "Malte" but I do not think it is of great consequence. I must say that I do not remember exactly how it was.

One can be inspired by an insignificant detail.

Certainly, I draw inspiration from literature, as I do from music, observation of my surroundings and all things within and without me, but the inspiration is, so to say, casual, incidental, fragmentary. For instance, three years ago I saw from a No 19 tram an old man at the stop at Unii Square in Warsaw, with a wisp of grey hair tousled by the wind. I have repeatedly tried to paint this wisp and place it in a picture, but I have never succeeded. When I finally make it (if I ever do), shall I have to entitle it in accordance with the original inspiration? What for? I have had a number of such fragmentary inspirations. I have recently dropped a painting half-way when I realized that it was almost literally my friend's drawing I had seen a few years ago, which artist is, in turn, blamed by critics for being under my influence. One can ask here who is under whose influence. I certainly did not imitate him consciously. But we are inspired by everything around us, though I do not think that it is intentional or fully realized.

Literary inspiration does not differ from other kinds of inspiration, it is on a par with them. What is more, it does not necessary have to be predictable, considering the expression of the work lying at its source. One can be inspired by an insignificant detail. For instance, from the rather strenuous reading of Hawkes's "The Lime Twig" I remember the frozen bomber at the beginning but I think it is because I had for some time felt tempted to paint old aeroplanes. Later was discouraged by a painting by Woodroffe with an old rusted bomber in the background. That is why I hate looking at other people's paintings. Anti-inspiration or being unable to paint something because it has been painted by someone else is even worse than a total lack of inspiration. Hence I was the happiest when I believed that I was the first in the world to arrive at certain ideas.

[Untitled, Zdzisław Beksiński, 1980]

Q: You absorb contemporaneity mainly or even solely through a music of violent impact. How does it affect your artistic vision?

Z.B.: Well, let us not exaggerate. I simply like music and listen to it while working. As for the contemporary, I perceive it as probably everyone else does, though it has little effect on what I do. Nor am I convinced that music really acts as a direct inspiration. For instance, pop music does not inspire me, but acts as a stimulant, like coffee or sugar. It is pure pleasure devoid of the element of mental experience. I rrjean thing is generally true, but certainly there are exceptions to this rule as there are to all other rules. When I paint to the sound of pop music, my body moves in away which makes work more difficult, so what I do appears quite senseless. But when I turn the volume down, I feel a lack of something without which I cannot work. As regards classical music, i can really speak about something bordering on inspiration. It simply seems to me that I think about a painting in terms of a late 19th century symphonic poem. And that is why I do not care what is going to be painted; the important thing cannot be expressed in words but I do hope I am able to convey it in my best paintings. It is a kind of elation which cannot be defined but which really exists and has found its most powerful expression so far in post-Wagnerian music. This is speaking generally, for I feel it also in the works of much later composers, such as Shostakovich, Honegger or Britten.

Q: What is the reference of your art to the output of great visionaries of the past, such as Gustav Moreau, Arnold Bocklin, Odilon Redon, Blake? What can you say about the Young Poland inspiration which is quite obvious to your public?

Z.B.: The question answers itself and I do not really mind. As a rule, I am compared with Linke and Bosch and in both cases I do mind. I do not accept all of Bocklin but his "Island of the Dead" made a great, unforgettable impression on me when I was a child and this impression survived until this day.

The message of painting does not dwell in the accessories but in the unspoken.

Q: In a number of your paintings and drawings, the chief role is played by symbols, signs or accessories such as the cross, skeletons, or a skull, which have functioned in art for ages but in a way differing according to the period. You use them in a stylistic version reminiscent of modernism or, at times, Romanticism. It is a conscious intention?

Z.B.: All I want to do is to paint. One cannot escape tradition. A painting as such, an object hanging on the wall, defined by its geometric shape, framed, looked at and commented upon is as a whole the result of tradition. Both contemplation of a work of art and conversation about a work of art, are elements of tradition, which have penetrated even conceptualism. Why, for Heaven's sake, should I, of my own free will, give up other traditional elements, such as the dim glimmer of varnish, composition of figures, and so on? From the very first pictures that I saw in childhood in churches and people's homes, I have gradually built up the idea of a painting in my consciousness. And I wish to materialize this idea. It can be done through opposition, irony, in inverted commas, from a distance and through persiflage, but it can be also done literally and naively. I use my accessories for the large part quite consciously because they are, in my opinion, linked up with the idea of a painting, linked as closely as the frame or the hook at the back. And what if I use a particular sort of accessories? I have not got so many. All the greatest pictures in the world resemble one another and it does not really matter what they represent. Personally, I prefer painting a fantastic, irregular ruin to a contemporary regular office building, the main reason being that in the former case work does not bore me. The message of painting does not dwell in the accessories but in the unspoken. At most, accessories or rather the preference for a certain kind of accessories reflect the artist's mental disposition. But I do not paint in ordertoinitiatespiritual contact.To bequite honest, I do not really know what it is all about. I simply feel an urge to paint And whether I have too much or too little imagination... I must say that I do not think much of imagination. A tree against a misty background means more to me if it is well painted than all of Magritte.

Q: Your work is strikingly uneven. Some paintings seem to unveil a mysterious, eery world, but there seems to be even more that annoy one for their banality. Do you classify your works according to your own hierarchy?

Z.B.: I would certainly not like to annoy anyone with banality. I believe that lam not banal, but that is only my own belief. Is it not a matter of reading false symbols into what I have painted? Quite naturally, I regard some paintings as good and some as poor. Good work is the fruit of good luck or a good period. I always want to paint well but I do not always succeed in doing so. I am speaking about my own judgement. A poor painting results from the chosen method on the one hand, and the chosen object on the other. As regards the latter, I often find half-way that I do no longer believe in what I am dqing. It happens as rule with figurative scenes and I feel as if I have suddenly seen the scene I am painting through a window and had to describe it in words. lt does not apply to landscapes with which there are formal problems but this is not the subject of the question. To return to what the public may find banal: I think that what happens is misinterpretation. When one paints real objects, each of them evokes a number of simple associations but not all of these associations are apparent. For instance, the first association evoked by the word fish is not the same with everybody. What will be the first association 1 for one person, may be the seventh association for another and the hundredth for yet another. A number of real objects painted in one picture naturally prompt an interplay of first associations, according to certain fixed schemes, e.g. the symbolic scheme or surrealist scheme after Magritte style. As I have often said, in my case notional associations are only a by-product resulting from the fact that I paint real or almost real objects which enter into mutual spatial relations in a painting, though not of a notional type. Certainly, the word fish evokes a certain primary association with me as well as with others, and if I paint a fish in certain surroundings, I cannot discard the entire baggage of associations, but nor do I, by any means, use them in a creative way. If I do not paint a red fish hanging from a balloon (which is something I do avoid), I believe that it is clear to everyone that a fish is a fish and nothing else. Nevertheless, if I paint dead fish that the sea has thrown on to the sand, which apparently is as natural as a tree against a misty landscape, because the fish are presented in a most plausible situation and environment, it does not mean that I have avoided the danger of response bordering on literary banality. Incidentally, I am describing a concrete work painted a few years ago which I have grown to loathe because of the commentaries speaking about the traditional "fish on the sand" or, still worse, "a protest against the danger of ecological catastrophe". But I did not think in this way originally; what I thought was quite simple: I painted the sea and the dead fish thrown ashore. And nothing else. And if I should ever paint a nude girl with a skull in her hand, it would be neither "love and death" nor "vanitas". Banality functions only as a by-product. Oncea painting has been finished I very often realize ex post facto, from public response and opinion that high brows have read something else into my work than I have.

[Untitled (commonly known as "Nevermore"), Zdzisław Beksiński, 1979]

Q: Enthusiasts of your art argue that it reveals the depths of an extreme existential experience. Opponents see it as a masterly show of a fairly stereotype horror. How would you verbalise the message it conveys?

Z.B.: I think that all I want is pretty paintings. Simply pretty. You may easily call me a poseur, it would not be the first time that I meet with such a question and such a reaction to my answer. But I really want to paint pretty pictures. At the source of my definition of a pretty painting lies a large Baroque or 19th century altar piece or a dark landscape in an old home, hanging in company of family portraits and other landscapes; in such a company there would undoubtedly be a place for a painting by Vermeer. That does not exhaust the subject but I am quite sure that I do not want to produce horror... I would find it a very nice compliment indeed if someone told me that what I paint is morbid. I am very strongly attracted to the morbid, which does not imply that I relish the common cold; what I mean is morbidity in 19th century understanding of the term. I mean something which attracted Thomas Mann. Hence, in some respects, Wojtkiewicz is closer to me than Vermeer, but only in some respects. Perhaps the synthesis for which I astrive is quite inconsistent and unattainable...

Photography

Want to see more? Explore one of the largest collections of Beksiński's fine art prints here.