About Alphonse Mucha - biography, facts, quotes, photography and more

"Art exists only to communicate a spiritual message."

- Alphonse Mucha

Early years

Alfons Maria Mucha, known internationally as Alphonse Mucha, was born in the town of Ivancice, Moravia (today's region of Czech Republic). His singing abilities allowed him to continue his education through high school in the Moravian capital of Brünn (today Brno), even though drawing had been his first love since childhood. He worked at decorative painting jobs in Moravia, mostly painting theatrical scenery, then in 1879 moved to Vienna to work for a leading Viennese theatrical design company, while informally furthering his artistic education. When a fire destroyed his employer's business in 1881 he returned to Moravia, doing freelance decorative and portrait painting. Count Karl Khuen of Mikulov hired Mucha to decorate Hrusovany Emmahof Castle with murals, and was impressed enough that he agreed to sponsor Mucha's formal training at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts.

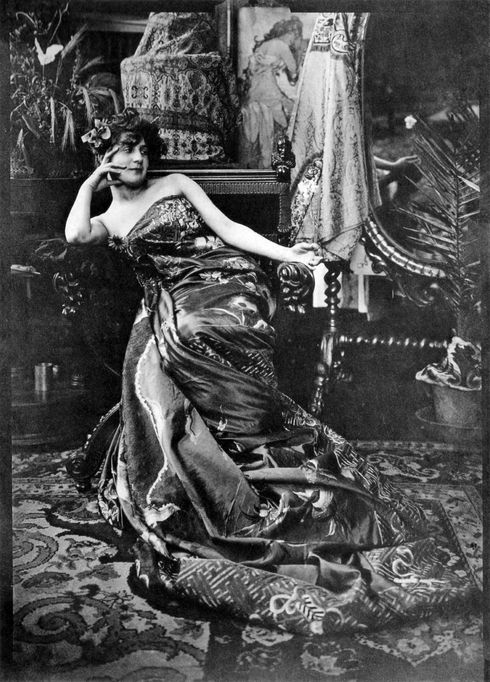

Mucha moved to Paris in 1887, and continued his studies at Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi while also producing magazine and advertising illustrations. Around Christmas 1894, Mucha happened to drop into a print shop where there was a sudden and unexpected demand for a new poster to advertise a play starring Sarah Bernhardt, the most famous actress in Paris, at the Théatre de la Renaissance on the Boulevard Saint-Martin. Mucha volunteered to produce a lithographed poster within two weeks, and on 1 January 1895, the advertisement for the play Gismonda by Victorien Sardou appeared on the streets of the city. It was an overnight sensation and announced the new artistic style and its creator to the citizens of Paris. Bernhardt was so satisfied with the success of that first poster that she entered into a 6 years contract with Mucha.

What is it, Art Nouveau?... Art can never be new.

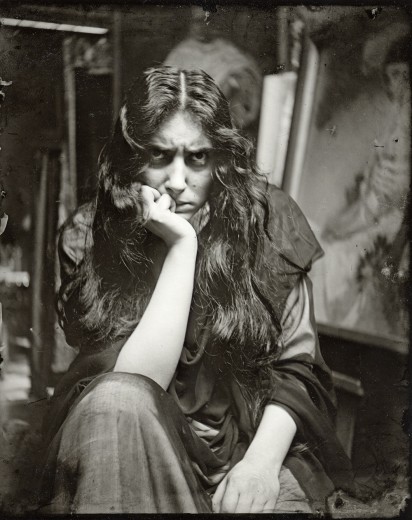

Mucha produced a flurry of paintings, posters, advertisements, and book illustrations, as well as designs for jewellery, carpets, wallpaper, and theatre sets in what was initially called the Mucha Style but became known as Art Nouveau (French for 'new art'). Mucha's works frequently featured beautiful healthy young women in flowing vaguely Neoclassical looking robes, often surrounded by lush flowers which sometimes formed haloes behind the women's heads. In contrast with contemporary poster makers he used paler pastel colors. The 1900 Universal Exhibition in Paris spread the "Mucha style" internationally, of which he said "I think [the Exposition Universelle] made some contribution toward bringing aesthetic values into arts and crafts." He decorated the Bosnia and Herzegovina Pavilion and collaborated in the Austrian Pavilion. His Art Nouveau style was often imitated. However, this was a style that Mucha attempted to distance himself from throughout his life; he insisted always that, rather than adhering to any fashionable stylistic form, his paintings came purely from within and Czech art. He declared that art existed only to communicate a spiritual message, and nothing more; hence his frustration at the fame he gained through commercial art, when he wanted always to concentrate on more lofty projects that would ennoble art and his birthplace.

["Rêverie" ("Daydream"), originally poster for "F. Champenois Imprimeur-Éditeur", Alphonse Mucha, 1897-1898]

Marriage

Mucha married Maruska (Marie/Maria) Chytilová on June 10, 1906, in Prague. The couple visited the U.S. from 1906 to 1910, when their daughter, Jaroslava, was born in New York City. They also had a son, Jiri (born on March 12, 1915 in Prague). There he expected to earn money to fund his nationalistic projects to demonstrate to Czechs that he had not "sold out". He was supported by millionaire Charles R. Crane, who applied his fortune to promote revolutions, and after meeting Thomas Masaryk, Slavic nationalism. The family then returned to the Czech lands and settled in Prague, where he decorated the Theater of Fine Arts, contributed the murals in the Mayor's Office at the Municipal House, and other landmarks of the city. When Czechoslovakia won its independence after World War I, Mucha designed the new postage stamps, banknotes, and other government documents for the new state.

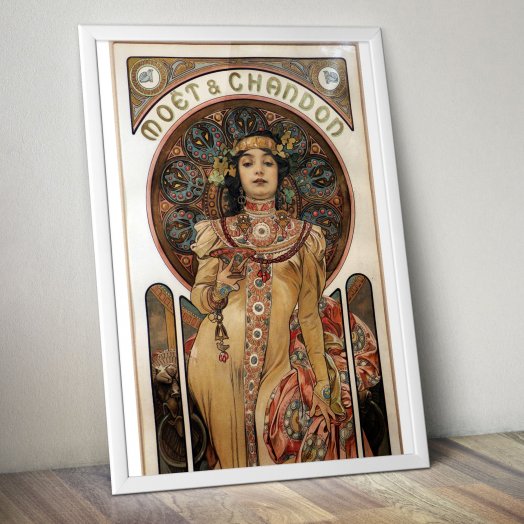

[Poster for "Moët & Chandon: Champagne White Star", Alphonse Mucha, 1899]

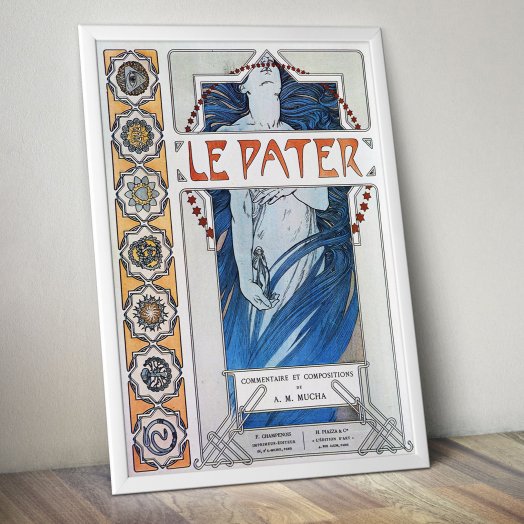

Le Pater

Mucha considered Le Pater his printed masterpiece, and referred to it in the January 5, 1900 issue of The Sun Newspaper (New York) as the thing he had "put [his] soul into". Printed on December 20, 1899, Le Pater was Mucha's occult examination of the themes of The Lord's Prayer and only 510 copies were produced.

Published in Paris on 20th December 1899 at the passing of the old century, it was meant to be Mucha’s message to future generations about the progress of mankind. Through the archetypal Christian prayer, he wished to present the way for man to reach the Divine Ideal, the highest state in the spiritual world.

Mucha conceived this project at a turning point in his career. According to his own account, Mucha was at that time increasingly dissatisfied with unending commercial commissions and was longing for an artistic work with a more elevated mission. He was also influenced by his long-standing interest in Spiritualism since the early 1890s and, above all, by Masonic philosophy. In January 1898, almost two years before the publication of Le Pater, Mucha was initiated into the Paris Lodge Les Inseparables du Progrès as an apprentice and after the independence of his homeland he was to become the highest representative of the Freemasons of Czechoslovakia. Mucha’s freemasonry was an outcome of his Spiritualism – the pursuit of a deeper Truth beyond the visible world. Through his spiritual journey Mucha came to believe that the three virtues – Beauty, Truth and Love – were the ‘cornerstones’ of humanity and that the dissemination of this message through his art would contribute towards the improvement of human life and, eventually, the progress of mankind.

["Le Pater", Alphonse Mucha, 1899]

In order to visualise his vision, Mucha analysed each of the seven verses of the model Christian prayer and reconstructed it in a set of three pages. The first page of each set, in colour, is the relevant verse in French and Latin, framed in a border sumptuously decorated with flowers and a symbolic female figure. The second page, also in colour, is Mucha’s own text, interpreting the verse and decorated with floral patterns. The third monochromatic page, printed in photogravure, contains a full-page allegorical drawing illustrating Mucha’s philosophical response to the verse. Throughout the pages, Mucha’s designs feature an abundance of Masonic symbols. The outcome was an exquisite book published in an edition of only 510 copies.

Le Pater was Mucha’s first manifest as an artist-philosopher and he regarded the book as his finest work. In 1900 Mucha exhibited the book and the preparatory drawings at the Paris International Exhibition and was deeply gratified when the illustrations attracted the attention of Emperor Francis Joseph I.

The Slav Epic

I will be able to do something really good, not just for the art critic but for our Slav souls.

Alphonse Mucha spent many years working on The Slav Epic cycle, which he considered his life's masterwork. He had dreamed of completing such a series, a celebration of Slavic history, since the turn of the 20th century; however, his plans were limited by financial constraints. In 1909, he managed to obtain grants by an American philanthropist and keen admirer of the Slavic culture, Charles Richard Crane. He began by visiting the places he intended to depict in the cycle: Russia, Poland and the Balkans, including the Orthodox monasteries of Mount Athos. Additionally, he consulted historians regarding details of historical events in order to ensure an accurate depiction. In 1910, he rented part of the castle in Zbiroh and began working on the series.

Mucha continued working on the cycle for 18 years, gradually submitting paintings to the city of Prague as he completed them. In 1919, the first part of the series comprising eleven canvases was displayed in the Prague's Clementinum. In his opening speech, Mucha stated:

"the mission of the Epic is not completed. Let it announce to foreign friends – and even to enemies – who we were, who we are, and what we hope for. May the strength of the Slav spirit command their respect, because from respect, love is born."

In 1921, five of the paintings were shown in New York and Chicago to great public acclaim.

In 1928, the complete cycle was displayed for the first time in the Trade Fair Palace in Prague, the Czechoslovak capital.

During World War II, the Slav Epic was wrapped and hidden away to prevent seizure by the Nazis.

Following the Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948 and subsequent communist takeover of the country, Mucha was considered a decadent and bourgeois artist, estranged from the ideals of socialist realism. The building of a special pavilion for the exposition of the Slav Epic cycle became irrelevant and unimportant for the new communist regime. After the war, the paintings were moved to the chateau at Moravský Krumlov by a group of local patriots, and the cycle went on display there in 1963.

Death

The rising tide of fascism in the late 1930s led to Mucha's works, as well as his Slavic nationalism, being denounced in the press as 'reactionary'. When German troops marched into Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1939, Mucha was among the first people to be arrested by the Gestapo. During the course of the interrogation the aging artist fell ill with pneumonia. Though eventually released, he never recovered from the strain of this event, or seeing his home invaded and overcome. He died in Prague on July 14, 1939 of a lung infection, and was interred there in the Vyšehrad cemetery.

[Poster for "Moët & Chandon: Dry Imperial", Alphonse Mucha, 1899]

Legacy

By the time of his death, Mucha's style was considered outdated. However, interest in his distinctive style experienced a strong revival in the 1960s (with a general interest in Art Nouveau) and is particularly evident in the psychedelic posters of Hapshash and the Coloured Coat, the collective name for two British artists, Michael English and Nigel Waymouth, who designed posters for groups such as Pink Floyd and The Incredible String Band.

In his own country, the new authorities were not interested in Mucha. His Slav Epic was rolled and stored for twenty-five years before being shown in Moravsky Krumlov and only recently has a Mucha museum appeared in Prague.

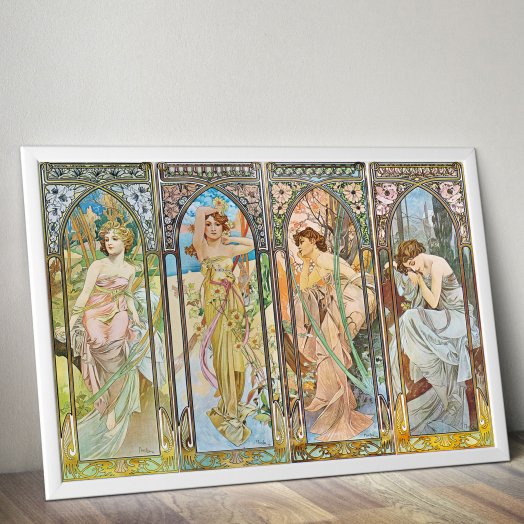

["The Times of the Day" (series), Alphonse Mucha, 1899]

Mucha's legacy has continued to experience periodic revivals of interest for illustrators and artists. It is a strong acknowledged influence for Stuckist painter Paul Harvey whose subjects have included Madonna and whose work was used to promote The Stuckists Punk Victorian show at the Walker Art Gallery during the 2004 Liverpool Biennial. The japanese manga artist Naoko Takeuchi released a series of official posters depicting five of the main characters from her manga series Sailor Moon mimicking Mucha's style. Another manga artist, the 1962 born Masakazu Katsura has also mimicked Mucha's style several times. Comic book artist and current Marvel Comics Editor in Chief Joe Quesada also borrowed heavily from Mucha's techniques for a series of covers, posters, and prints. Grindcore and sludge metal band Soilent Green used a picture by Mucha for the cover of their album Sewn Mouth Secrets.

Among his many other accomplishments, Mucha was also the founder of Czech Freemasonry.

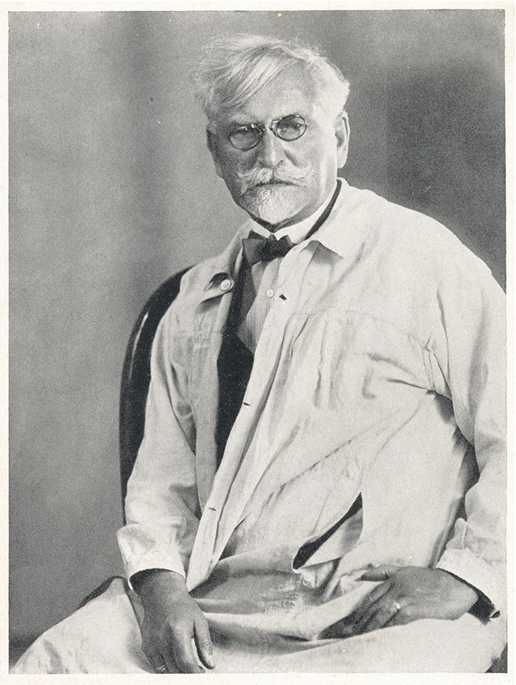

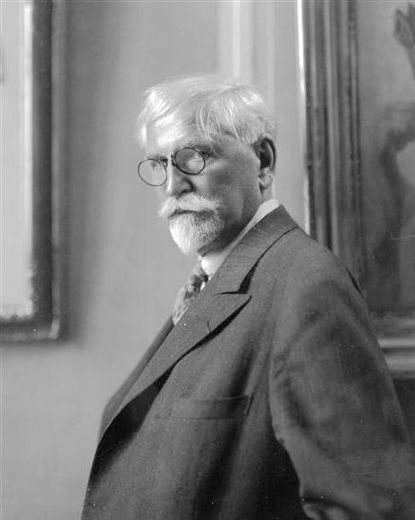

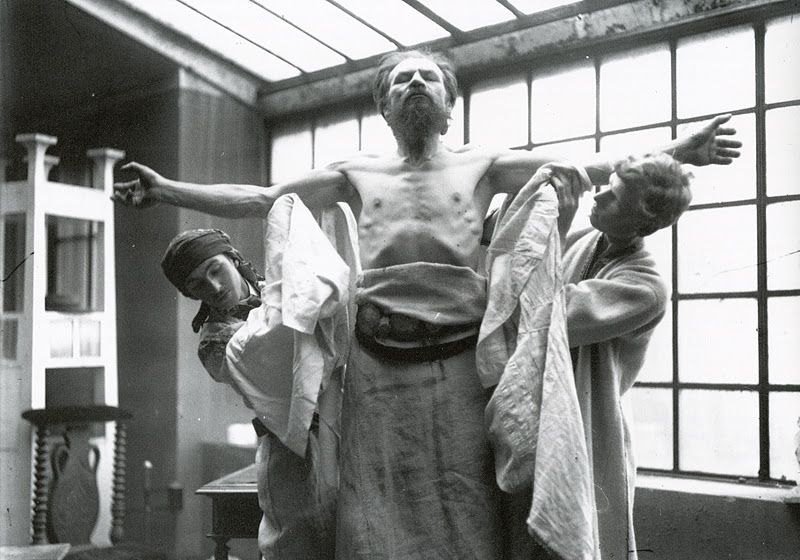

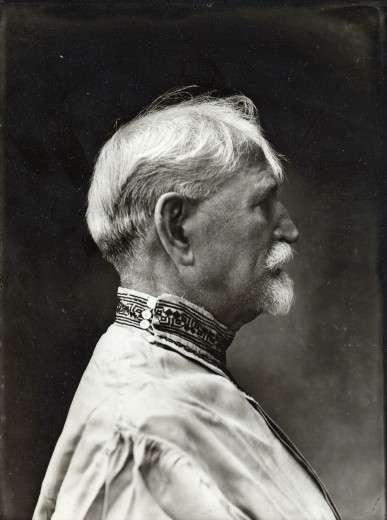

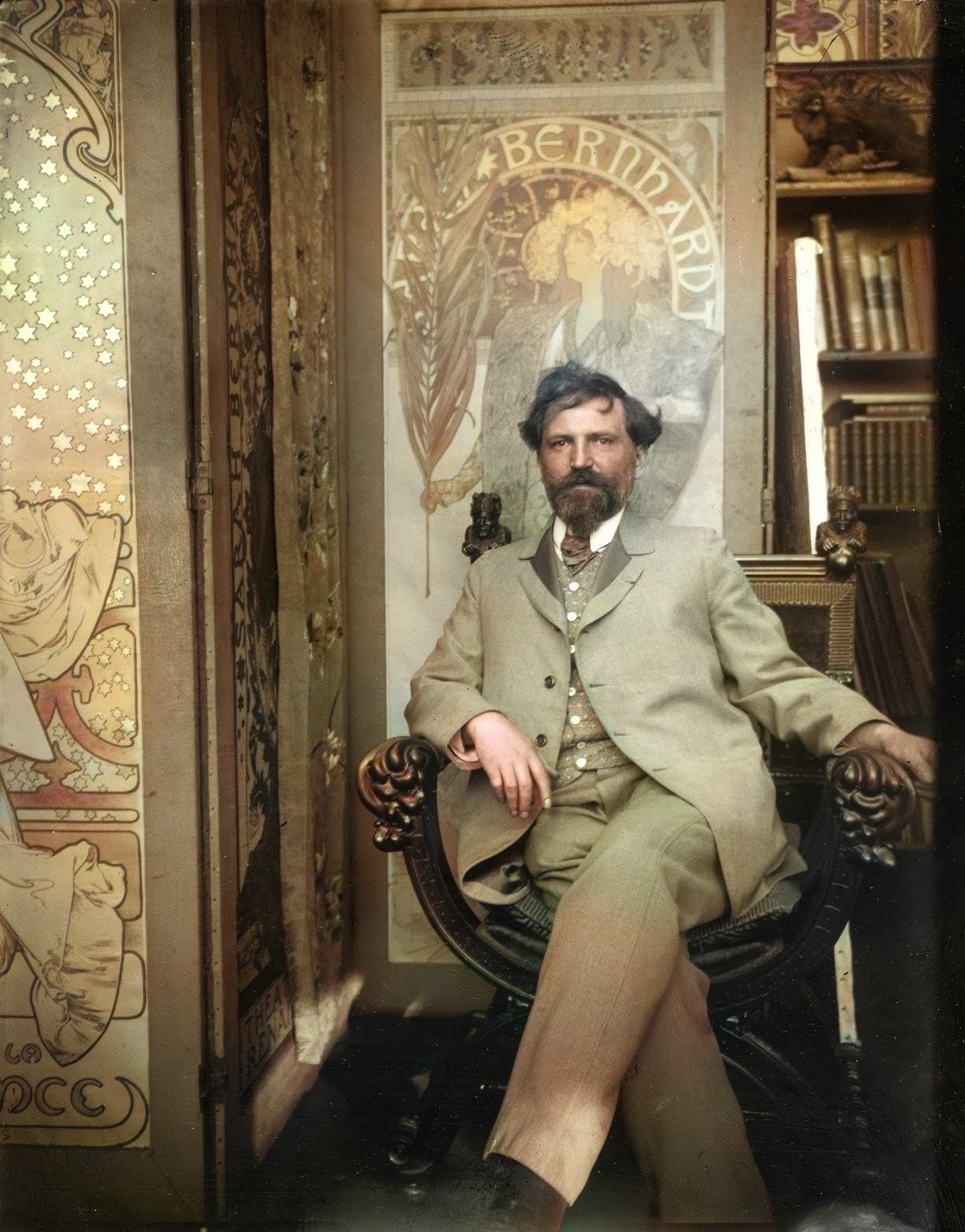

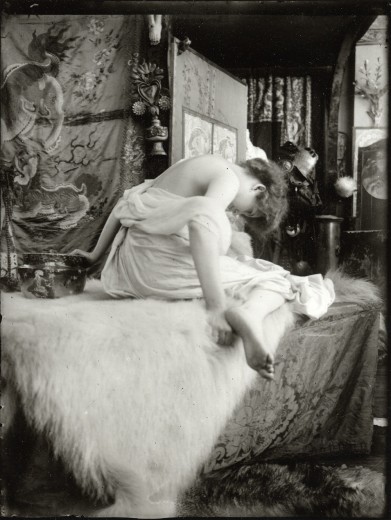

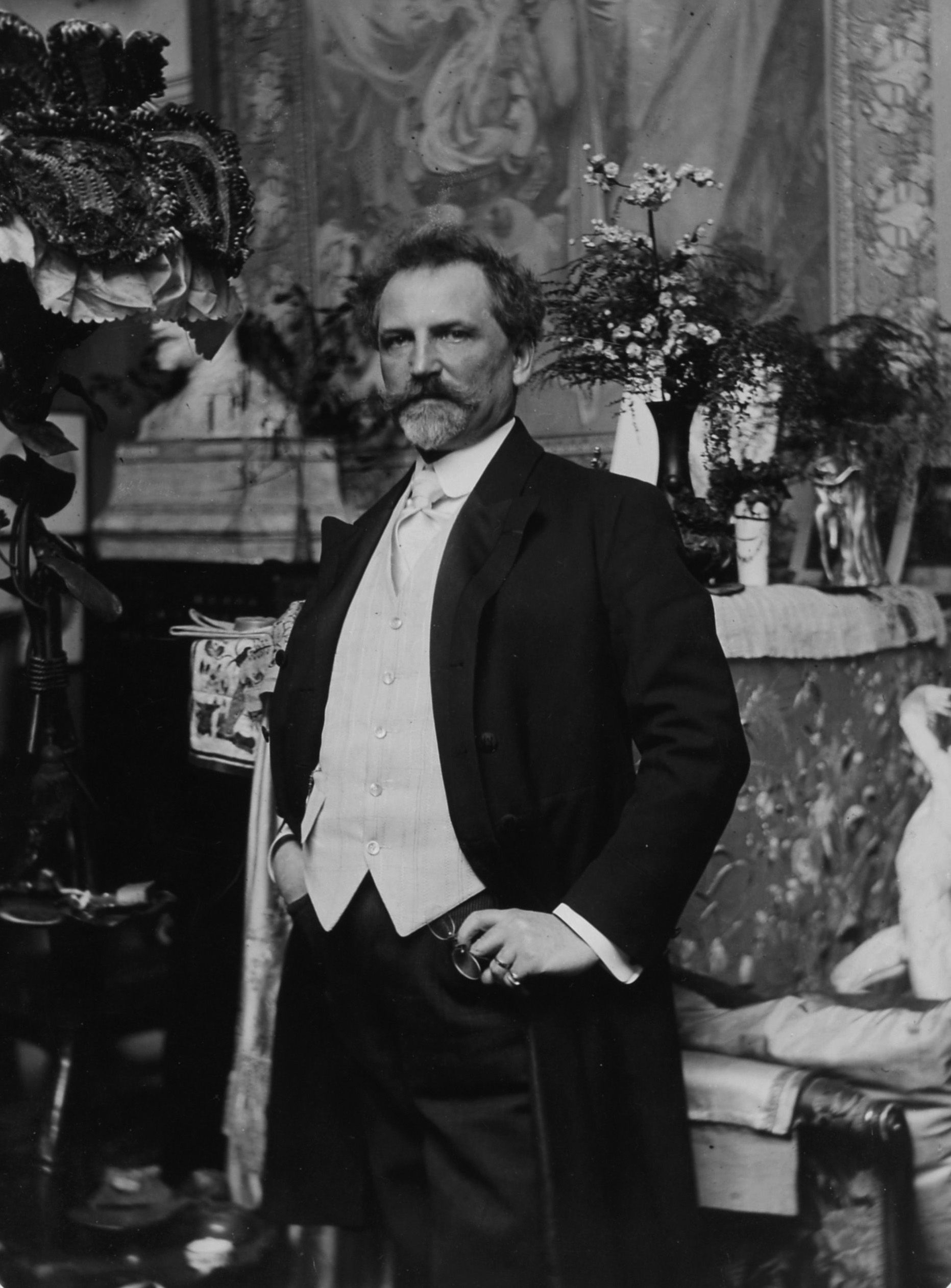

Photography

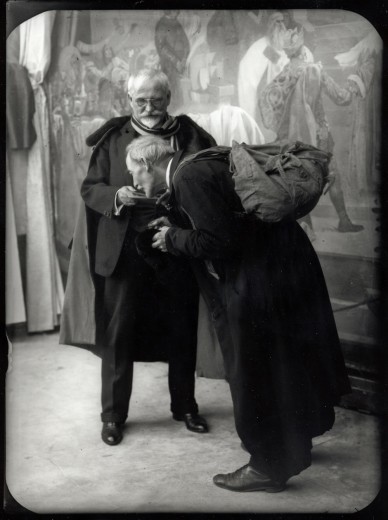

Mucha began to take photographs in the early 1880s, probably in Vienna, with a borrowed camera. It was not until he had gained some recognition in Paris and sufficient funds that he purchased his first camera. Mucha’s photographic output grew dramatically after his move to a large studio in the rue du Val de Grâce in 1896. In the new studio, where he had considerably more light thanks to large windows and a glass ceiling, he photographed on a virtually daily basis.

Want to see more? Explore one of the largest collections of Mucha's fine art prints here.